Making decisions is a difficult and tiring thing you have to do all day long. Let’s talk about why decision making is difficult, and how to make it less difficult. But first, let’s talk about how to evaluate decisions.

How to evaluate good vs bad decisions

First: all your moral guidelines? Throw ‘em out. That’s not what determines a good decision versus a bad decision. Or at least that’s not how I define a good (or bad) decision, and this is my blog, so I get to make the rules.

A good decision is a decision helps you get what you want in a way that aligns with who you want to be. A good decision works with your values and your desires.

A bad decision doesn’t. A bad decision might work with your values but not your desires, or vice versa. A bad decision might get you something you want, but in a way that turns you into someone you don’t want to be.

Let’s say that you want to have more money.

- A good decision would help you make more money in a way that feels good to you: doing something you enjoy doing, providing value, working with people who matter, working on fulfilling projects, etc.

- A bad decision would help you make more money in a way that doesn’t feel good or betrays your values, or both: doing work you hate with people you don’t care for just because there’s a bigger paycheck is an example of the former. Cheating or stealing or lying to be successful and make more money is an example of the latter.

Of course, whether a decision is good or bad depends on your values and desires. A good decision for me might be a bad decision for you, and vice versa.

Why decision making is tough

You’re always working with incomplete information.

No matter how much you know, there’s a limit to the knowledge you can acquire and/or the amount of knowledge you can process.

When you know you’re working with incomplete knowledge, there’s room for insecurity and indecisiveness. Ignorance is bliss. Knowing your own ignorance is paralysis.

What if you’re missing a key piece of information that would change your perspective? Lack of knowledge (or, more accurately, being aware of your lack of knowledge) creates stress and uncertainty in decision-making.

Like it or not, you’re an emotional creature.

I don’t like it, but here we are.

“Most of us think of ourselves as thinking creatures that feel, but we are actually feeling creatures that think.” [Source]

We mainly use our logical/analytical brain systems to justify our emotional responses or instincts.

This isn’t really a bad thing:

“Despite the growing reliance on “big data” to game out every decision, it’s clear to anyone with a glimmer of self-awareness that humans are incapable of constantly rational thought. We simply don’t have the time or capacity to calculate the statistical probabilities and potential risks that come with every choice.

But even if we were able to live life according to such detailed calculations, doing so would put us at a massive disadvantage. This is because we live in a world of deep uncertainty, in which neat logic simply isn’t a good guide. It’s well-established that data-based decisions don’t inoculate against irrationality or prejudice, but even if it was possible to create a perfectly rational decision-making system based on all past experience, this wouldn’t be a foolproof guide to the future.” [Source]

However, in a culture that prizes logic, certainty, and rationality, we feel kind of bad about making instinctive or emotional decisions.

We certainly don’t want to explain them our decision making process in emotional terms:

- “Why should we invest? Well, I have a good gut feeling about it.”

- “I’m making this important decision based on some emotions I have.”

Yeah…

And, of course, our emotions or instincts aren’t always good.

Some emotions and instincts will lead us to great short-term, instant gratification decisions that hurt our long-term health or happiness. Other times, we have certain values that conflict with our emotions or instincts.

It helps to have some tools or standards we can use for a more reliable decision making process.

Your willpower is limited.

You have a certain amount of willpower. Yes, you can develop more, but this takes time and focused effort. In the meantime, you have what you have, and every decision you make uses willpower.

Lots of decisions means you deplete your willpower.

Using your willpower on decisions that are unimportant may mean you don’t have willpower left for the decision that do matter.

Sometimes it’s not about priority (important v non important) but about timing. I’m an early-morning person: I wake up, I go, I’m ready, energized, and focused. I can trust myself to make what I’ll call good decisions

By mid-afternoon, good decisions are getting tougher.

By evening, I better have a plan, a routine, and most of the decisions already made or I am going to make a lot of bad ones.

Your decisions cost something.

Decision making has a time and energy cost.

Some decisions have a far-reaching effect. Some decisions are complex and important. Some decisions merit a fairly hefty time and energy cost.

Most decisions don’t.

Most decisions are about everyday stuff, or about choosing between two mostly equal options. It’s easy to pour time and energy into decisions, if we don’t stop to think about it.

We always want to make the best decision.

We forget that 1) there’s often no reliable way to determine which decision is the best and 2) the measurable difference between one Okay Decision and one Slightly-Different-But-Still-Okay Decision is negligible.

How to improve your decision making

There are three approaches to a better decision making process:

- Make fewer decisions

- Make faster decisions

- Make better decisions

Which approach is best depends on the kind of decision you’re making. If it is an important decision with far-reaching consequences, focus on making a better decision (not a faster decision). On the other hand, if it’s a decision that doesn’t matter much (like What should we eat for dinner?), then focus on making faster and/or fewer decisions.

How to make fewer decisions

Create routines

Routines are the easiest way to lessen the decisions you have to make. They allow you to bundle up a whole pile of everyday, detail decisions (when to wake up, what to wear, what to eat, etc.). When you create a routine, make all the decisions in that bundle once, and keep using the same decision over and over. Eventually it becomes automatic. You’re not consciously making decisions: you’re performing a routine. If you design good, helpful, healthy, enjoyable routines, then your quality of life increases as you stick to your routines without much cost in terms of willpower or conscious effort.

Set defaults

Defaults are preset decisions that you can use whenever needed. For example, if you want to spend less time and energy deciding what to have for dinner, pick a few default dinners. Keep the ingredients on hand. Defaults work particularly well for repeating but irregular decisions, such as where to eat out, what to eat when you eat out, or which airline to use.

Limit your options

The classic example is the limited wardrobe: make a few decisions about what you’ll wear, buy duplicates, and now getting dressed involves much less decision-making. You can do the same in other areas, such as diet, budget, entertainment, travel, socializing, etc.

Delegate

Get someone else to make the decision for you. A trusted expert, someone who has experience, someone who has a broader perspective, a knowledgeable friend. Maybe it’s someone who has less emotion involved and can be a bit more objective.

Assign

Divide the decision-making responsibilities by assigning areas to individuals. Partner 1 handles decisions about food, and Partner 2 handles decisions about the car. Whatever makes sense. This also eliminates the time spent deciding who’s going to decide. You can also take turns: Person A makes the calls for this day or week or month, Person B takes it on next.

How to make faster decisions

Limit optimizing

Our brains want to make the best use of energy, conserve as much as possible, and get maximum return for every bit of energy spent. But our brains are not so good at seeing that not all things have to be optimized. If you spend energy optimizing something that has a very limited amount of potential payback, you’re not being efficient. Pick areas that deserve the optimization energy: areas that are meaningful, enjoyable, important; things that repeat frequently; or decisions that have a significant impact on the quality of your work, life, relationships, etc.

Highlight those important areas—and the significant decisions you make inside of them—and give them time and attention for optimizing. Don’t optimize your other decisions.

5 minutes only

A good rule of thumb that I picked up somewhere: If you won’t remember this in 5 years, don’t spend more than 5 minutes worrying about it. Translate that into “don’t spend more than 5 minutes deciding about it.”

Follow your preferences

Pay attention to your preferences and, unless they’re damaging or destructive, just go with your preferences. You prefer wine to beer? Then stick with wine. You prefer wearing bright colors? Then shop for those colors and ignore the other options.

Avoid scarcity paralysis

Sometimes indecision comes from the fear that this will be your one-and-only chance to have/do whatever it is. That’s hardly ever a real situation. Remind yourself that you’ll have other chances: “This time, I will…. “ and then fill in the blank with a decision for right now, for this time.

Choose the opposite

If you are tired of your preferences, then go with… the opposite of what you normally prefer. Or the opposite of what you chose last time: “Last time I did X, so this time I’ll do Y.” Or really, any other factor can lead to an opposite, and you can choose the opposite, and revel in the duality of life and a quickly made decision.

Mood match

Check in with how you feel. “What do I need? How can I take care of myself?” If you’re stressed, anxious, uncertain, then ease up and choose what is familiar. If you’re feeling stable, supported, at ease, then branch out and experience something new.

How to make better decisions

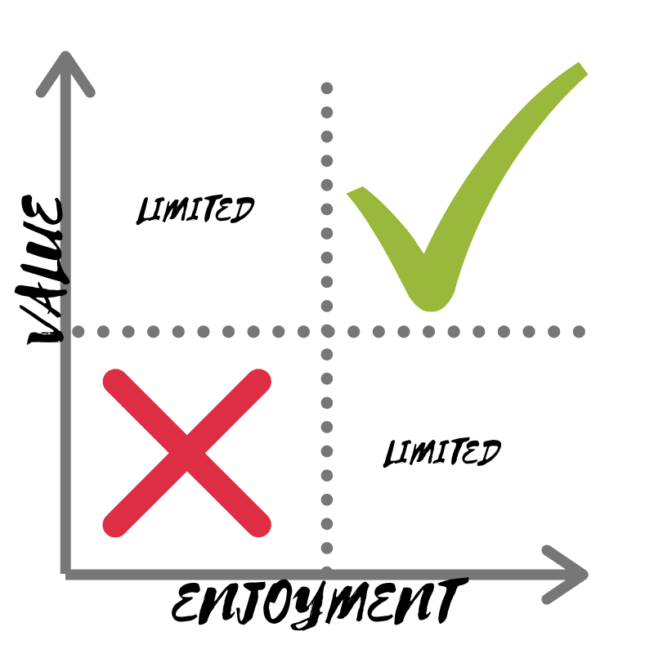

Use the value/enjoyment matrix

It looks like this:

Aim for that upper right quadrant. Automatic YES to anything that is both high value and high enjoyment. What is value? That’s up to you. What is enjoyable? Also up to you.

Avoid the lower left quadrant. Automatic NO to anything that is low value and low enjoyment. Why would you… why would you even do that stuff?

Limit the time you spend in the other two quadrants. Or seek a balance. Or at least think about the value/enjoyment ratio before you choose something.

Write a pro/con list

I think this works best if you make it as long as possible. Or force yourself to spend a little more time than you want to thinking about it. Then tead what you have on your list, and think about which pros and cons actually matter to you. Make your decision with those in mind.

Find the ideal outcome

Then reverse engineer it. What does the ideal outcome look like? To reach the ideal outcome, what actions must take place? What must be finished? Who do you need to become? What matters and what doesn’t?

If this were easy…

This is another helpful question: What would this look like if it were easy?

Because—a beautiful piece of news, here—not everything worthwhile has to be difficult. Asking how it looks if it’s easy may help you notice easier paths, more resources, or help you figure out that you want to do something else entirely.

Crunched timeline

One of the basic productivity laws tells us that there should be an equal amount of peanut butter and jelly on a pb&j sandwich.

Wait, no, that’s not it.

Ah, yes, now I remember: the task will expand to fill the time you give it. So give it—the task, the decision—a much shorter timeline. A ridiculously short timeline. Then, with that timeline on you, make decisions about how to carry it out.

Avoid the dichotomy

We tend to think in dualities: A or B.

While opposites are nice, there are more than two options for almost any decision. If you’re agonizing over which option is the right choice, step back and look for alternate options. Don’t see it? Create it. Option C.

Go back to why

What’s the purpose? What do you hope to achieve? What’s the output? Why are you spending time/energy on this thing?

If you can nail down the why, all you have to do next is find the next step, the one that leads you closer to the Why: the simplest action, the smallest move forward.

Follow the fear

Question the negative forces: what am I avoiding? What am I hiding? What is the rush? What is the urgency?

Then think about how you can flip that perspective.

How can you take power? How can you move toward something good instead of away from something bad. It’s more fun to be proactive than resistant.

What’s the next step?

All you really need is one small move. Find it. Take it. It’s in the doing of Step 1 that you see clearly what Step 2 is.

Sometimes our decision paralysis isn’t about the very next decision, but about the unknown of what follows it. But here’s the thing: you only get there by moving forward. You can’t predict it. So find one small step, take it, and then you’ll decide about the next step after that.

Of course, ultimately, reality is something we make up as we go, time doesn’t exist, matter is mostly empty space, and, speaking of matter, nothing really matters. So… don’t think too much about it.

Annie Mueller is a writer, reader, seeker of growth, and transplant to Puerto Rico, where she lives with her best friend and their four children. Her crash course in self-discovery came from experiencing job loss, financial devastation, Hurricane Maria and its aftermath, and major surgery—all in less than a year. She writes about creativity, personal growth, and spirituality; runs Prolifica, a content management consultancy for small teams and solo professionals; and sends out a popular weekly newsletter about feelings and freelancing. You can find more of her work on her website.

Image courtesy of Alex Green.