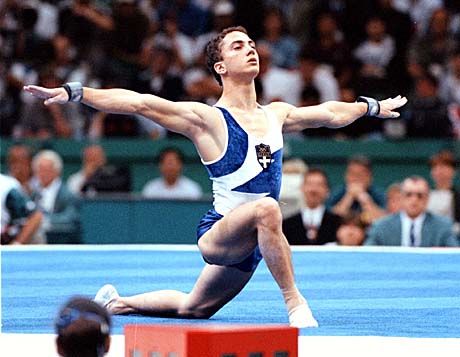

Melissanidis became Greece’s first gold medalist in 90 years with this performance in the floor exercise.

One of the great joys of being a writer is that, through your books, you get to meet some pretty amazing people. One of those in my world is Hermes (Ioannis) Melissanidis from Greece. Hermes won a gold medal in gymnastics at the Atlanta Olympics. Here’s the video if you’ve never seen it:

I met Hermes because of Gates of Fire. He wrote to me, telling me that he once had to perform in a gymnastics final when he had a broken rib. He was going to withdraw, but he happened to have Gates in his gym bag and he was reading about the Spartans. He competed and won. I asked him how he got into the sport.

When I was four or five, I saw gymnastics on the television for the first time. It blew my mind. I went straight to my mother and father and announced to them, ‘That’s what I want to do. I’m going to win a gold medal in the Olympics.’ My family are all doctors, so they naturally said no. They thought I was crazy. There was no way they would let me train for hours and hours a day for years and years just to learn a few tricks on the rings or the uneven bars or the pommel horse or the floor exercise.

So I went on a hunger strike. I stopped eating. I told my parents I would not take another bite until they agreed to let me train. I refused food for three days. They tried to tempt me with ice cream and chocolate, but nothing would make me bend. Finally on the fourth day, my mother and father said okay, they would let me train in gymnastics—but I could not neglect my studies and I must still go on to medical school. I said okay. We made an agreement.

So many aspects of this story are amazing to me, I hardly know where to begin. First, how fortunate Hermes was to find his passion so young—and to recognize it and embrace it without fear and without hesitation. Second, a hunger strike. What five-year-old even thinks about such a thing? Can you imagine this little tyke defying his parents like that? That’s what Rudy Tomjonovich would call “the heart of a champion.” Third, Hermes was a pro. At four or five years old, he was already a professional. He didn’t want to play or dabble at gymnastics; he was ready to commit full-time to years and years of killer training. He was in for the long haul—and with all his heart.

After I won at the Atlanta games, the Greek journalists of course were very excited. One came up to me with a microphone in my face and asked with great enthusiasm, ‘How does it feel to produce the performance of a lifetime here when you needed it most? How did you achieve that peak moment of greatness?’

I was so angry. I had to bite my tongue not to say something I would regret. Because I could see that this journalist had no understanding of athletes or of performance. So I smiled and gave the answer she wanted. But what I wished to say was this: ‘Don’t you understand that this was not the performance of a lifetime? I have performed this floor exercise in practice ten thousand times. Five thousand times I have done better than this! I did not have to exceed myself or go beyond my limits. I have trained for years to reach this level. This is it. This is what I am capable of every day.’

We’ve been talking in this space about amateurs and professionals—and the difference between the two. Hermes was a pro at four years old, and I can tell you, from what he has done in his subsequent career (he is acting now, based in London) that he has not deviated one iota from that mindset. [He did become a doctor, by the way, at the same time he was taking home gold in gymnastics.] I asked Hermes once about his diet. What sorts of food did he eat to support the incredible expenditures of energy in training and to build up the strength that a gymnast needs. I expected him to say he ate three porterhouse steaks a day with liver-and-whey shakes at every meal.

I have glass of whole milk for breakfast with a little honey and some royal jelly. For lunch a salad, maybe with some fish. Dinner, chicken and a salad.

That’s it? That’s what your coaches prescribe? How can you train that hard, all those hours, on just that small amount of food? Hermes touched one finger to his temple. He smiled. “It’s all up here,” he said. We can cite the commitment of a pro, the dedication, the application of will, the drive to succeed. All these are present with Hermes, that’s for sure. But the heart of the story to me goes back to when he was four or five. Love of the game. Hermes saw gymnasts on TV for the first time, and he knew at once: “That’s what I want to do.” Everything since has been simply reinforcement.

Steven Pressfield was born in Trinidad, B.W.I. and educated at Duke University. He is the author of The Legend of Bagger Vance, Gates of Fire, The War of Art and a number of other historical novels, set mostly in the ancient world. In 2008, the city of Sparta in Greece made him an honorary citizen. He lives in Los Angeles.